“Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” is Wrong—NOW Stop Using It

“Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs” is the most famous theory of motivation, but I reject it and encourage you to do the same.

Some of my colleagues have taken a more conciliatory stance in which they do some mental gymnastics in order to avoid negating this popular idea (Kenrick, Griskevicius, et.al., 2010; Streight, 2022; Wahba & Bridwell, 1976), while others have their own critiques (Fowler, 2014; Visser, 2020; Martela, 2020).

I have four key objections to “Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs”: the first two are based on incoherence, the third is based on the evidence, and finally, the existence of a thoroughly researched, highly effective, and well-established replacement seals the deal.

Also, I suspect that trying to use it may feed into and reinforce existing teacher biases that are potentially hazardous to students.

Taking my objections and the potential for counterproductive application together leads me to conclude that it should be abandoned forthwith and only regarded as an historical curiosity.

Maslow Before Bloom?

In education circles there is a catchy phrase: Students have to Maslow before they can Bloom.

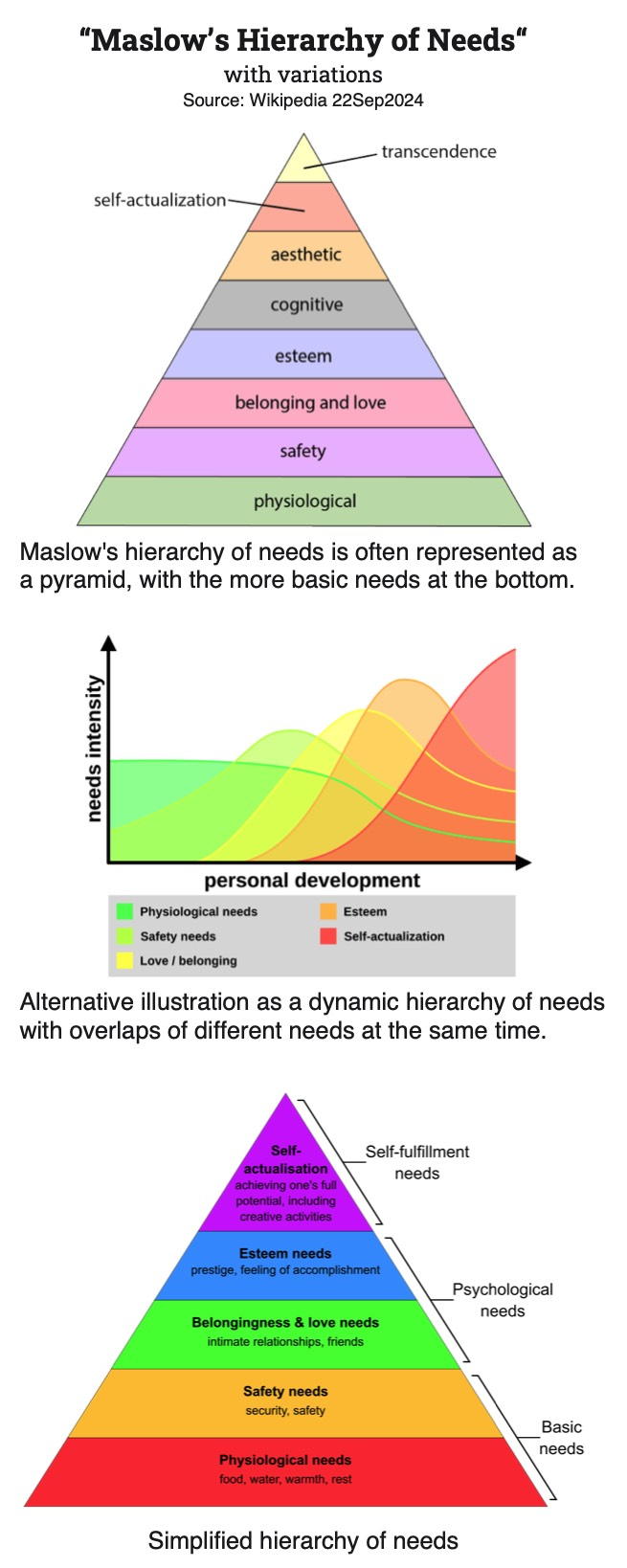

Bloom refers to another hierarchy usually called Bloom’s Taxonomy.

According to the Wikipedia page for it, “The taxonomy divides learning objectives into three broad domains: cognitive (knowledge-based), affective (emotion-based), and psychomotor (action-based), each with a hierarchy of skills and abilities.”

(The claim that each domain constitutes a hierarchy is dubious, but I leave that analysis to others, such as Carl Hendrick)

The idea behind the catchy phrase is that students have to have their basic needs attended to before they can do cognitively demanding work.

But that is not true except in the most extreme circumstances.

(Here’s a replacement: Agency before academics. You can delve deeper into that one by reading my book The Agentic Schools Manifesto.)

The research into primary psychological needs (which will be discussed later) has shown that they are interrelated, but not hierarchical (Ryan & Deci, 2000b).

For instance, let’s consider a student wrestler’s need for water.

Let’s assume that this high schooler is preparing for a highly competitive meet.

In order to lose weight he is dehydrating himself.

We can reasonably expect that this dehydrating wrestler would be able to function for some time as a human being even if his functioning as a student would deteriorate.

His learning would get shallower, but his dehydration was accomplishing a purpose that he valued.

If “Maslow’s Hierarchy” was right, then we should be expecting him to have ceased to be a functional human being before he could accomplish his purpose.

If a hierarchical relation existed, his dehydration, the thwarting of a “lower” need, should have precluded his desire or ability to achieve the “higher” need.

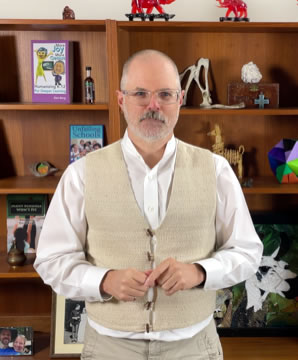

“Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs” as a Hierarchical Pyramid

“Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs” is usually presented as a pyramid which is interpreted as a suggestion that work starts at the bottom and you move up as you go; you can't skip a level.

This same notion would also presumably apply to the model of cognitive tasks that originally comprised “Bloom’s Taxonomy.”

Regarding “Maslow’s hierarchy” it is intuitively obvious that suffocating stops all else from mattering. But the question is whether that holds true for other needs.

Before we can honestly deal with that question we must ask, What counts as a need, anyway?

This is where Maslow made his first and most fatal error.

He speculated on what seemed like plausible needs to him.

Unfortunately, several of his speculations were too vague to be useful to subsequent scientists.

When researchers take their task of studying his model seriously they are forced to come up with more precise definitions that they can make use of in their research (Taormina & Gao, 2013; Tay & Diener, 2011; Wahba & Bridwell, 1976).

That form of mental gymnastics is buried in their papers; meaning that translating that “science” into consistent and replicable applications is unnecessarily difficult.

Defining needs is where the founders of Self-Determination Theory, the most successful model of human motivation in the world today, made one of their most valuable contributions.

They didn’t simply define the needs, they defined the criteria by which needs should be judged and categorized in order to be taken seriously (Deci, & Ryan, 2000; Ryan, & Deci, 2000a; Ryan, Deci, Vansteenkiste, & Soenens, 2021; Ryan, & Sapp, 2007).

They did the hard work of creating a set of preliminary rules for distinguishing primary needs from secondary, derivative, and particular needs.

Scientists now and into the future are thus able to judge all the candidate needs that have come along and, if necessary, can also refine the rules for making those judgments.

To be fair to Abraham Maslow, it was recently reported that he did not actually claim that needs were strictly hierarchical (Littrell, 2012) nor did he even come up with the pyramid presentation (MacLellan, 2019), which is why I’ve consistently put quotes around the whole phrase.

The “hierarchy” that bears his name is wrong in several ways, primarily because it has not withstood repeated tests of scientific scrutiny.

Attempts to “update” or “expand” the “hierarchy” have not saved it from creating fundamental misunderstandings about human needs (Kenrick, Griskevicius, Neuberg, & Schaller, 2010; Wahba & Bridwell, 1976).

The implication of presenting needs and components of learning in pyramid formats is that something must serve as the foundation and you can't get to the other things higher up until after you have that foundation laid.

The “basics” are foundational, right?

After the kids get those “basics” they will be more capable of doing the interesting stuff that is more advanced.

Those erroneous implications are not trivial; they are misconceptions that can be harmful in school settings.

Problematic Applications of “Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs”

In schooling, the LACK of hierarchical relations is particularly important to understand due to the ways that the traditional notion of “back to basics” tends to be implemented.

The basics are typically delivered by simplistic rote learning processes in which students and teachers find little to no meaning (Mehta, 2018).

Children are assumed to be lingering at the bottom of both Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy and Maslow’s hierarchy.

If a school leader is committed to “Maslow before Bloom” with an eye to ensuring that students get the “basics,” they are inviting their staff to use their pre-existing biases to decide what constitutes appropriate activities and instructional demands for their students.

Given the ambiguity of the science behind “Maslow’s Hierarchy” that school is probably going to self-reinforce their existing arbitrary preconceptions about the limitations of their “difficult” students and unfairly restrict their opportunities to learn.

The meaningLESSness of most “basic” instruction is the thwarting of a derivative need (Martela, Ryan & Steger, 2017).

Those curricular and pedagogical choices made under the spell of a “back to basics” mantra will tend to preclude enabling children to do activities they personally find meaningful until after they have acquired those “basics.”

The meaningLESSness of those activities will cause their learning to be shallower than it otherwise could have been.

In addition, the negative associations arising from being coerced into doing them could delay or prevent their acquisition of those skills.

In the arena of literacy those negative associations might lead to rejection of reading altogether so that students grow up to become illiterate citizens.

But, it can also lead to students that grow up to become aliterate citizens.

Aliteracy is when a citizen has the skills but not the desire to read.

Illiteracy and aliteracy are equally bad educational failures for a pluralistic democratic society like ours.

The meaninglessness is derived from the neglect or thwarting of the teachers’ and children’s primary psychological needs, described below.

Meaninglessness does educational harm, even in the absence of any other observable sources of physical or emotional harm.

Striking the right balance between the student’s relationship to the subject and their competence in it is crucial to deeper learning.

To avoid potentially harmful applications of “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” scientists should give up on the extraordinary mental gymnastics required to preserve the model.

It is better to abandon the “hierarchy” altogether.

Replacing “Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs”

In Self-Determination Theory there were initially three criteria for classifying a need as primary (there are at least six that have been added since).

The key initial criteria were 1) the effects of a need cannot be neutral with regard to well-being, 2) a need must apply cross-culturally, and 3) the need cannot be derived from any other needs.

Non-neutrality means that meeting a need has to have a positive effect on well-being while thwarting or suppressing it has a negative effect.

The cross-cultural requirement means that there cannot be any human beings who have well-being without it.

Finally, needs that naturally follow from other needs are derivative, not primary.

Meaningfulness, as mentioned before, is a derivative need.

Needs are secondary when they have positive well-being consequences when they are satisfied, but have no effects on well-being when they are thwarted or suppressed.

Beneficence (a.k.a. benevolence) is a secondary need.

The category of particular needs are those that are unique to an individual, situation, or cultural group.

Medical life support systems are a particular need for individuals who are severely sick or injured.

Despite having created a truly compelling image that will likely go on misleading people for many more years to come, Maslow got it wrong.

Now is the time to abandon the “hierarchy of needs.”

It is a mistake to use the notion of hierarchical relations among the needs.

(Except in the most trivial chronological sense that thwarting the need for air can kill a person in minutes, thwarting the need for water can kill in days, food in weeks, and exposure to the elements can kill across all those times scales depending on the circumstances.

Thwarting psychological needs does not directly kill you, but the mental dysfunctions that result from having those needs thwarted might.)

Returning to SDT for a moment: according to a study of the validity and strength of Self-Determination Theory as a scientific theory from a sociologist looking at it from outside the community using a nine-part analytic tool SDT is a solid, well-supported model (Joseph, 2023).

It is not perfected, yet.

It got less than perfect scores in the areas of conceptual clarity (3 of 5), philosophical assumptions (4 of 5), and scope (2 of 5).

“Results indicate that SDT is theoretically sound. It has strength in terms of coherence, historical evolution, testability, empirical evidence, usefulness for practice, and human agency,” with scores of 5 out of 5.

It is also highly productive with a rapidly growing literature, which is another sign of robustness, which is all in sharp contrast to “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.”

To summarize my view: I respect “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” because it set forth a model that people responded to; like most of Sigmund Freud’s work, it was usefully wrong.

I reject “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” because 1) there is a far better scientific model of how needs affect motivation, 2) there is little evidence that it is useful, 3) it is not fully coherent.

Self-Determination Theory is the replacement I recommend.

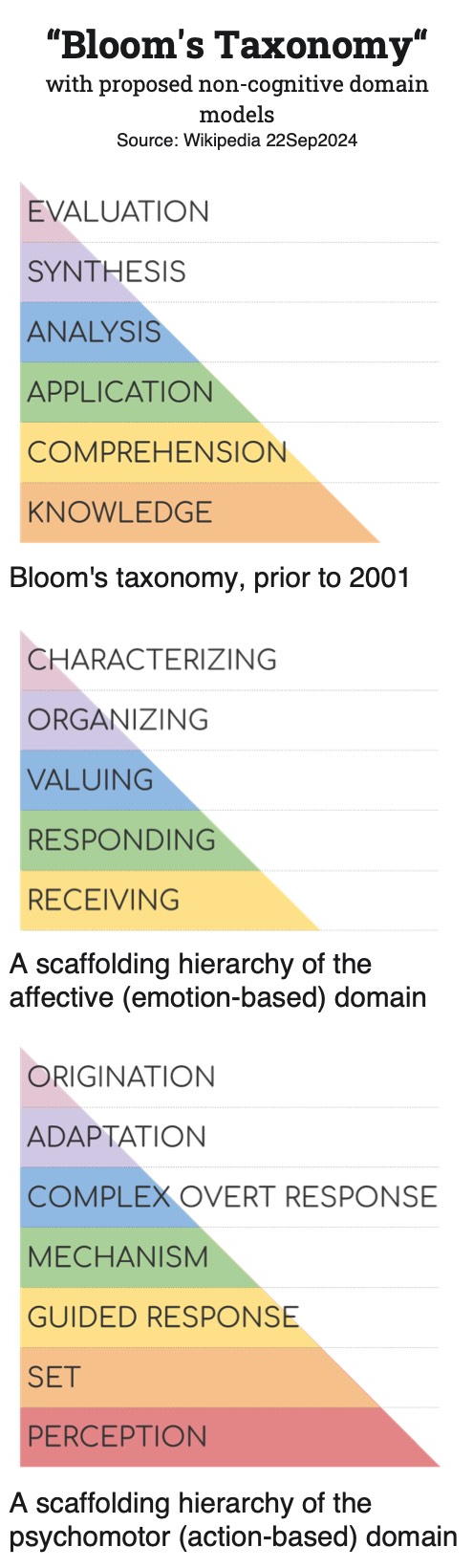

For those who need a replacement image, below is one I created riffing on ideas from Barry Scott Kaufman and Frank Martela: The sailboat of needs.

Enjoy!

References

- Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

- Joseph, R. (2023, June). A critical appraisal of Self-Determination Theory through the prism of the Theory Evaluation Scale. Paper presented at the 8th International Self-Determination Theory Conference held in Orlando, FL, USA.

- Kenrick, D.T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S.L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 292–314. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369469.

- Littrell, R.F. (2012) Academic anterograde amnesia and what Maslow really said. Auckland, New Zealand: Centre for Cross Cultural Comparisons Working Paper CCCC 2012.3, http://crossculturalcentre.homestead.com/WorkingPapers.html.

- MacLellan, L. (2019, April 10). “Maslow’s pyramid” is based on an elitist misreading of the psychologist’s work. Quartz. https://qz.com/work/1588491/maslow-didnt-make-the-pyramid-that-changed-management-history/

- Mehta, J. (2018, January 04). A Pernicious Myth: Basics Before Deeper Learning. Retrieved January 21, 2019, from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/learning_deeply/2018/01/

- Martela, F., Ryan, R.M. & Steger, M.F. (2017). Meaningfulness as satisfaction of autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: Comparing the four satisfactions and positive affect as predictors of meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9869-7

- Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2021). Building a science of motivated persons: Self-determination theory’s empirical approach to human experience and the regulation of behavior. Motivation Science, 7(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000194

- Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000a). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000b). The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 319–338.

- Ryan, R. M., & Sapp, A. R. (2007). Basic psychological needs: a self-determination theory perspective on the promotion of wellness across development and cultures. In I. Gough & J. A. McGregor (Eds.), Wellbeing in Developing Countries: From Theory to Research (pp. 71–92). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taormina, R.J. & Gao, J.H. (2013) Maslow and the motivation hierarchy: Measuring satisfaction of the needs. American Journal of Psychology 126(2), 155-177. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.2.0155.

- Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 101(2):354-65. doi: 10.1037/a0023779

- Wahba, M.A., & Bridwell, L.G., (1976) Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 15(2), 212-240. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6.

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com