Is Motivation Boosted By Achievement?

Does the claim “achievement boosts motivation” stand up to scientific scrutiny?

That claim was made in a post by Greg Ashman in November of 2020 (cited below).

From the perspective of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) research tradition that has been studying the psychology of motivation for over four decades, it is a colloquially true-ish claim, but is scientifically vague.

In order to give teachers good instructional advice, the model of motivation and the relationship between motivation and achievement that informs that advice needs to be sufficiently precise to discern effective need supportive teaching practice from ineffective need thwarting or neglectful teaching practice.

I am not an expert on instruction, but I am an expert on motivation.

Notice that I put “effective” with “need supportive.”

Ashman argues for an effective instructional practice (direct instruction/explicit teaching) but does not indicate any awareness of the importance of need support, which is problematic.

It is probably possible to use his preferred techniques in either need supportive, need thwarting, or need negligent ways, which, as you will see, is important.

The problem is that assuming motivation is a singular monolithic concept that obeys a mental on/off switch, as appears to be common in education circles and not just in Ashman’s writing, suggests that motivation might be irrelevant or unimportant to achievement.

It invites perpetuation of teaching practices that might be counterproductive.

More specifically when direct instruction/explicit teaching is promoted because “achievement boosts motivation” (as Ashman does, cited below) the well-being consequences of that technique are being glossed over.

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with using direct instruction/explicit teaching, as long as the well-being of students and teachers is not diminished in the process.

That can happen if the primary needs of the students and teachers are thwarted or neglected by that technique or the way in which it was made to happen in a particular classroom.

Motivation Basics

Let’s start with the most basic possible understanding: Motivation is about how energy is allocated.

Need satisfaction generates energy, motivation allocates that energy, and engagement applies that energy to the situation in which the person is situated.

The whole energy generation (needs), allocation (motivation), and application (engagement) process changes over time.

It changes from moment to moment as the feedback from the situation changes.

How the human energy system operates has consequences for well-being and learning.

In a classroom the behaviors of the teacher and a student’s peers can be powerful components of the over all feedback process that a student experiences and those experiences will affect their well-being and learning.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is the model of motivation with the most thorough grounding in empirical research in the world today (citation below).

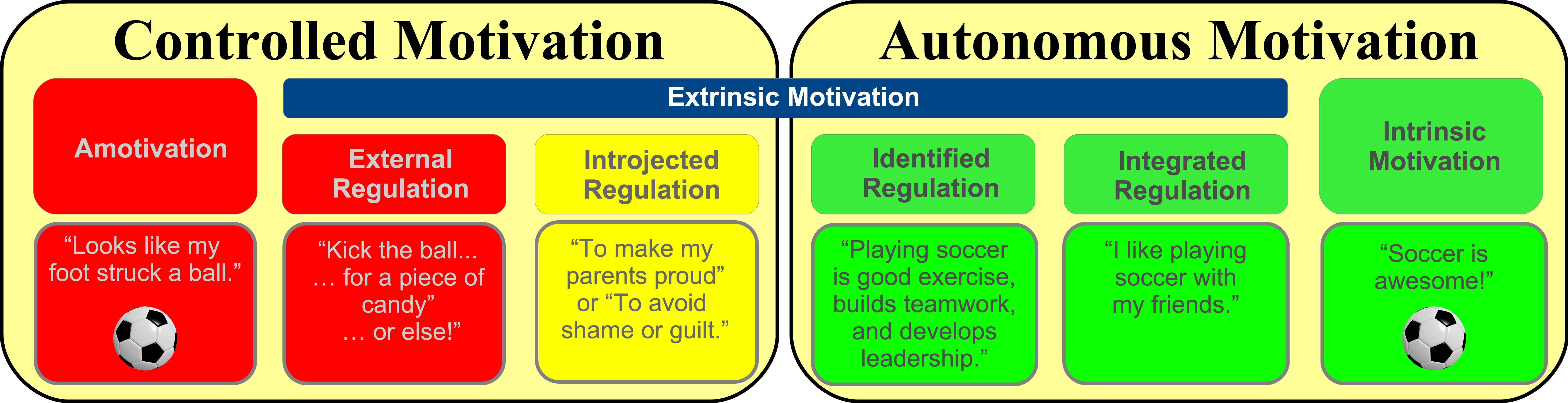

The SDT model of motivation can be understood at two levels; as a dichotomy or a six-part spectrum.

The dichotomy consists of autonomous motivations that have positive effects on well-being and controlled motivations that have negative effects on well-being.

The six-part spectrum is divided in half down the middle by the dichotomy, illustrated below.

The problem with claiming that “achievement boosts motivation” is that achievement that leads to controlled motivations would be having immediate negative well-being consequences and could be bad for long-term engagement with the task and maybe the subject, too.

While an achievement that leads to autonomous motivations would be an unqualified good.

In order to properly appreciate the “bad” possibilities you have to understand that the causal source of motivation is the degree of satisfaction of primary needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence.

These needs are categorized as primary because they cause humans to experience increases in well-being when they are satisfied and experience diminished well-being when they are neglected or thwarted.

Thus, these needs are the causal source of both well-being and motivation.

This sharing of the causal source for both well-being and motivation makes the misrepresentation of motivation into a more consequential factor than most people writing about motivation appreciate.

It would be surprising if educators are OK with compromising the well-being of children in order to practice their teaching.

Sensible parents would never send their child to a school that routinely suffocates, dehydrates, starves, or recklessly exposes their students to the elements.

Sensible teachers would never work for a school like that for both moral and educationally practical reasons.

There is no reason to believe that a sensible parent or teacher would want to compromise the psychological well-being of children either.

However, they might accidentally compromise the psychological well-being of children because of bad advice that promotes attaining achievements without regard for the well-being consequences of the instructional practices employed.

Examining the Motivation Claims

Now we shall examine Ashman’s claim in more detail.

Here it is as presented in his post on November 13, 2020:

"Achievement boosts motivation

"Many people seem to think that we need to motivate students to make them learn.

"This is often couched in terms of ‘engagement’.

"However, this idea may have cause-and-effect the wrong way around, or at least may neglect an important pathway.

"One Canadian study [conducted by SDT researchers, cited below] found that, for primary school children, maths achievement predicted later motivation but maths motivation did not predict later achievement.

"Pekrun and colleagues [cited below] found more of a two-way relationship, but they still found a clear achievement-to-motivation pathway.

"This makes sense.

"Getting better at something is motivating.

“Conversely, the classic approach of trying to excite students about, say, science by doing a funky demonstration, may not be as effective as we think.

"We may generate so-called ‘situational’ interest but this is unlikely to feed forward into a long-term interest in science on its own.

"Instead, we should probably investigate the most effective ways of teaching science – such as explicit teaching – to ensure students learn more, gain a sense of achievement and become motivated as a result.”

“[W]e need to motivate students to make them learn.”

SDT does NOT make this claim.

SDT DOES claim that motivation has important consequences for the quality and depth of learning, but it is not the causal source of it.

I must note that in psychology learning is assumed to be occurring as long as a person is alive and awake.

The most frequent lesson is that existing models of the world and the self are good enough for now.

Only under specific circumstances, e.g. when the mind is open, certain concepts are being challenged, and perhaps other conditions, does deeper conceptual change happen.

Therefore, learning is shallow by default and only becomes deep in rare instances.

This seems to be in contrast with a tendency in education circles to speak of learning as if it only counts when it is deep.

This is problematic because a significant amount of shallow learning consists of actively incorporating information into existing models without making deep conceptual changes.

It seems the height of arrogance to presume that with the right technique deep learning is going to consistently result from instruction.

There is no doubt in my mind that direct instruction/explicit teaching is valuable, but it is not a silver bullet for deep learning.

“This is often couched in terms of ‘engagement.’”

In SDT, needs and motivation are regarded as the causal sources of the conceptually distinct phenomena of engagement, not couched inside it.

Remember that needs generate energy, motivation allocates it, and engagement applies it.

But engagement also occurs in multiple forms that have different learning consequences.

The forms that are well established in the literature on engagement are behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic.

(A recent study, cited below, suggested that emotion and cognition might be better thought of as motivational processes, so we will not address them here.)

If engagement is merely behavioral then that will mean learning is shallower.

In more precise terms, disengagement is a sufficient condition to cause learning to be shallow.

However, agentic engagement is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for learning to be deep.

Deep learning can be prevented by ineffective instruction and probably a variety of other situational factors.

Thus, my counterclaim against “achievement boosts motivation” is that direct instruction/explicit teaching and other instructional means of attaining achievement can be highly effective, but only when the motivations of the students and teachers are autonomous and their engagement is agentic.

Those particular characteristics of the experience that a student is having indicate that the mind is sufficiently open to facilitate conceptual changes, if necessary, and even when that is not necessary the learner will be better able to incorporate into their existing mental schemas the information that they are getting from their experiences.

“Getting better at something is motivating.”

SDT mostly agrees but to be more precise you would have to specify that “getting better at something” actually means having a perception of competence which satisfies that primary human need.

It is possible that “getting better” in terms of improved objective performance could be accompanied by a lack of perceptions of competence, which would mean diminished well-being and de-motivation.

While the claim is “true” in colloquial terms, it is too vague in scientific terms.

In Conclusion

To be generous let’s interpret Ashman’s use of the term “achievement” to mean that attaining that outcome would involve the satisfaction of some combination of the needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence.

In that light his claim could be regarded as correct.

However, I can readily imagine forms of achievement that were attained through merely behavioral engagement with an abundance of controlled motivations thereby diminishing a student’s well-being which results in a lot of shallow learning.

I can readily imagine that scenario because it is a pretty good description of much of my schooling experience when I was a child and young adult.

In that light his claim is false.

Once again the claim is plausible when taken colloquially, but fails in more precise scientific terms.

The fact is that Ashman’s claims are too vague to be useful.

Therefore, I hope that the claim will be modified to better reflect the reality that achievements that are attained through primary need satisfying teaching and learning practices boost motivation.

As stated in a review of meta-analytic studies of SDT in educational settings, “Higher autonomous motivation among students is associated with greater academic achievement….” (cited below)

On the other hand, achievements attained through primary need thwarting or neglectful teaching and learning practices diminish motivation.

I understand that it is much easier to communicate with a wider audience by using vague colloquial terms.

But I suspect that teachers, presumably the intended audience, can handle more precision. More important they will probably appreciate having a better understanding of how motivation actually works.

This is especially the case when the increased precision enables them to focus on the causal factors that produce better motivation, specifically supporting the satisfaction of primary psychological needs (independent of what instructional technique is used).

References

Ashman’s Original Claim:

https://gregashman.wordpress.com/2020/11/13/education-research-the-evidence/

Ashman promoting explicit teaching:

31Oct23 - https://fillingthepail.substack.com/p/explicit-teaching-is-inclusive

15Aug24 - https://fillingthepail.substack.com/p/unpacking-explicit-teaching

SDT as the leading model of motivation:

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2021). Building a science of motivated persons: Self-determination theory’s empirical approach to human experience and the regulation of behavior. Motivation Science, 7(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000194

Canadian Study:

Garon-Carrier G, Boivin M, Guay F, Kovas Y, Dionne G, Lemelin JP, Séguin JR, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Intrinsic Motivation and Achievement in Mathematics in Elementary School: A Longitudinal Investigation of Their Association. Child Dev. 2016 Jan-Feb;87(1):165-75. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12458. Epub 2015 Nov 9. PMID: 26548456.

Pekrun and colleagues:

Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., Marsh, H., W., Murayama, K. and Goetz, T. (2017) Achievement emotions and academic performance: longitudinal models of reciprocal effects. Child Development, 88 (5). pp. 1653-1670. ISSN 0009-3920 doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12704 Available at https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/65981/

Engagement Papers:

Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Jang, H. (2020). How and why students make academic progress: Reconceptualizing the student engagement construct to increase its explanatory power. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 62(101899). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101899

Reeve, J., & Shin, S. H. (2020). How teachers can support students’ agentic engagement. Theory Into Practice, 59(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1702451

“Higher autonomous motivation among students is associated with greater academic achievement….”:

Ryan, R. M., Duineveld, J. J., Di Domenico, S. I., Ryan, W. S., Steward, B. A., & Bradshaw, E. L. (2022). We know this much is (meta-analytically) true: A meta-review of meta-analytic findings evaluating self-determination theory. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11–12), 813–842. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000385

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com