What is a Moral Imperative in Education?

What is a moral imperative in education?

Before we tackle that question in an education specific way, imagine rescuing a child from imminent danger.

If the action you take to save the child results in other people dying unexpectedly, then were you wrong to have acted on that imperative?

Are we responsible for the unintended consequences of morally justifiable actions?

Even though, as educators, our moral imperatives do not usually involve death, we do owe it to our students to get clear about what our normal moral obligations are and how to respond appropriately.

What is a Moral Imperative on TV?

Season thirteen of Gray’s Anatomy provides us with a hyper-exaggerated scenario to prime our intuition pumps.

In episode twenty-three highly driven and successful surgical intern Stephanie Edwards was kidnapped at scalpel point by a rapist.

In the course of the kidnapping they ended up in a suite of rooms off a stairwell when a lockdown trapped them and coincidently an 8-year old girl named Erin.

When the rapist turned his back to Stephanie while trying to set off the fire sprinklers with a flaming piece of cloth at the end of a pole, Stephanie picked up a container of alcohol and doused him with it.

There is a dramatic pause while he realizes his predicament.

Then, of course, he quickly catches fire but as he is perishing he collapses next to several large canisters that are also extremely flammable and … KA-BOOOM.

Thus Stephanie achieved her immediate goal, but with severe consequences.

After being found by a colleague and some first responders in episode twenty-four when they get to the ER she is performing chest compressions on Erin and says,

“I deep-fried a rapist.

“I dove through a wall of fire.

“I did not do all of that so that this little girl could die.”

In the end the little girl Erin was saved, Stephanie lived, and no one else died, but Stephanie was so severely burned that she ended her surgical career to pursue life beyond the hospital.

Stephanie inadvertently made a moral trade-off, she gave up her health and career in an attempt to end a clear and present danger to her and the child for whom she went to heroic lengths to save.

No reasonable person can argue against the moral imperative presented by the clear and present danger to which Stephanie was responding.

However, it is also not difficult to imagine how vigorously the same actions could be harshly evaluated if by happenstance the rest of that wing of the hospital had been filled with a bunch of innocent people when it exploded, instead of being empty.

Thus her deep-fried rapist maneuver could easily be reframed as foolishly desperate.

When moral imperatives are involved, whenever we have the luxury of doing so, we need to reflect carefully on what constitutes a reasonable response.

What is a Moral Imperative for Michael Fullan?

I concur with Michael Fullan that the education of children involves a moral imperative, which is exactly why he used that phrase in the titles of two of his books.

My point in bringing up Stephanie Edwards dramatic choices is that we educators need to be more thoughtful about how we handle our moral imperatives than she was able be in the heat of the moment.

If we don’t take the opportunity to understand our situation properly when we have the time to consider it deeply, then we run the risk of responding in ways that cause more harm than help.

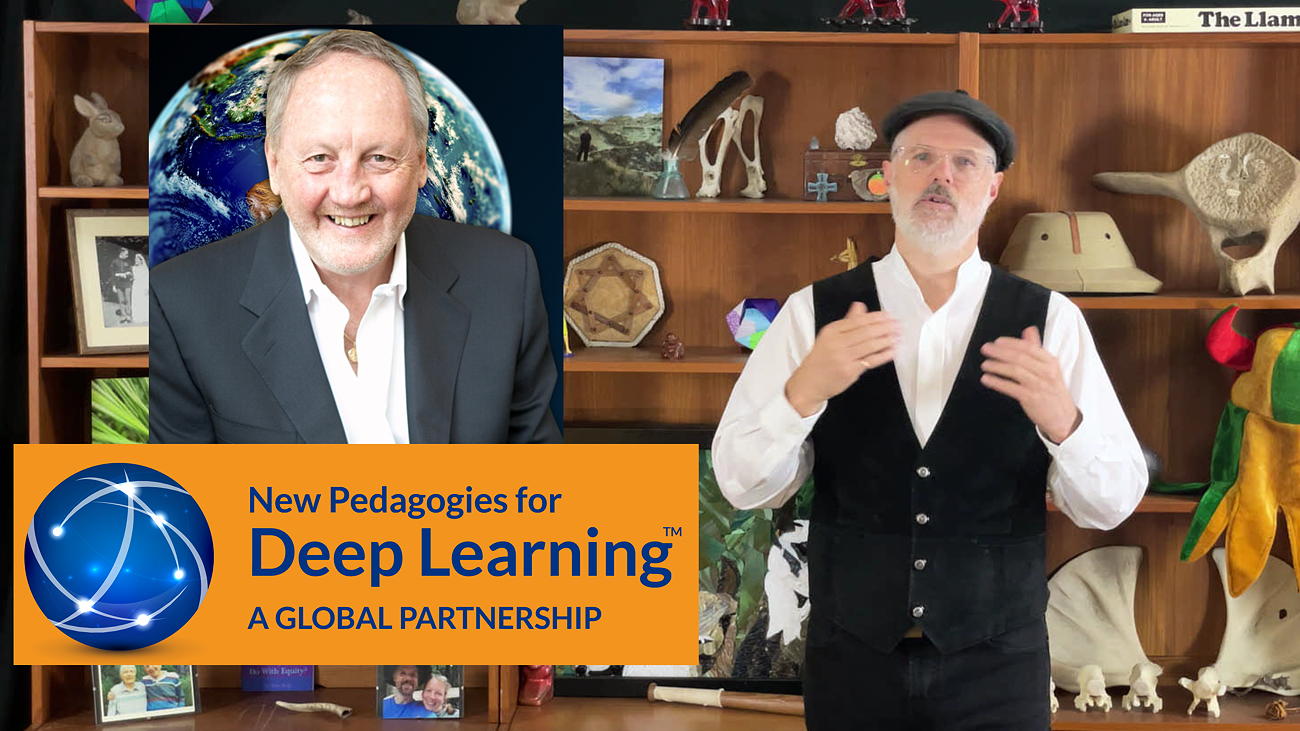

Michael Fullan is a highly prolific author on the subjects of principalship and educational change leadership.

Plus he is doing good work all over the world to further deeper learning.

Unfortunately, he did not bother to define what he meant by the moral imperative in education and his books are so focused on managing the context of school transformation that I am still not sure how exactly he would answer the question, What is a moral imperative in education?

His ideas about the role of the principal in systemic change are good, but, because there can be some confusion about it, his books would have been much more satisfying if he had been clear about what he meant by the phrase “moral imperative”.

Sometimes morality gets conflated with religion.

Strictly speaking morality has nothing to do with religion even though some religious folks believe that their religion is the source of their morality.

I trust the scientists who have studied morality when they say that humans were moral beings long before religions existed and we would remain so even if religion ceased to exist.

Those religious folks are wrong about the source of their morality.

Another confusion about morality is the idea that it boils down to following rules.

This is also not the case.

Morality is about imaginatively thinking through your understanding of a situation to arrive at a course of action that will best ensure the well-being of those who will be affected by your decisions.

Once again this is not an idle speculation, it is based on a combination of scientific research and deep philosophical consideration of how to interpret the relevant scientific facts.

In particular I rely primarily on the works of George Lakoff, Mark Johnson, and Owen Flanagan, though I believe that the views of Jonathan Haidt, Michael Sandel, Sam Harris, and Joshua Greene are probably also consistent with this view.

So, since Michael Fullan was clear about it, I want to think through two experiments and use them as a basis for figuring out what the moral imperative in education is.

With a clearer understanding of the moral imperative for educating children, we should be able to make better decisions about which strategies are, ultimately, better for achieving that goal.

Intuition Pump #1: The Science Experiment

We will start with a scientific experiment and then consider a thought experiment.

The science experiment is about how people recover from negative events.

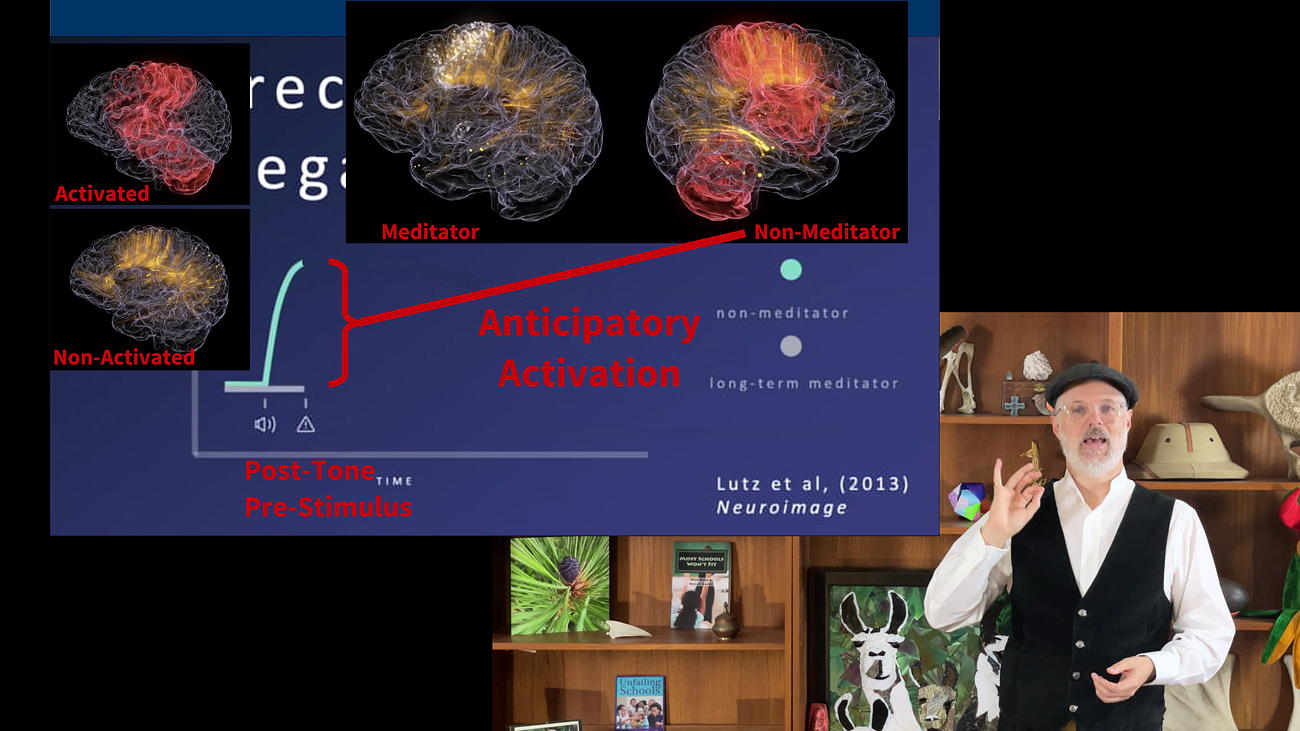

The experiment involved hooking folks up to a brain scanner, playing a tone then, after a 10-second delay, causing the subject to experience a painful, but harmless, stimulus.

When the brain’s pain network is activated it looks like this.

The non-activated pain network looks like this, which suggests that other areas are activated instead.

There were two kinds of subjects for the study:

non-meditators, who had no training in meditation and long-term meditators, people who’ve been trained and practiced meditation for years.

The light blue line indicates the brain activation for the pain area in non-meditators while the light purple line indicates activation for the meditators.

Of course they start out on the same level.

Then the tone sounds and the brain activation patterns start to deviate from each other.

The meditators stay at their baseline level while the non-meditators have an anticipatory activation response.

They are anticipating the experience of pain.

Then when the pain stimulus actually occurs the meditators joined the non-meditators in experiencing pain, in fact they might experience it just a little bit more intensely.

After the stimulus is done then the meditators recover to their baseline pretty rapidly.

The non-meditators, on the other hand, have their pain centers still going so that they recover much more slowly.

But after sufficient time has passed both meditators and non-meditators return to their baseline equanimity.

Notice that they begin and end in the same place but they have had different journeys during this time.

Now let’s think about what this means for education.

First of all an educated person is someone who perceives accurately, thinks clearly, and acts effectively on self-selected goals and aspirations that are relevant to their situation, without necessarily being aware that those things are going on.

In this case we are going to think of not just a singular pain event but about any adverse life events that may occur.

When an adverse life event occurs then we want to know whether they are perceiving accurately and thinking clearly.

When we look at how people respond to the painful stimulus we can see that there’s an area that I’ve colored red here and that area is the difference between negative sensations of pain and negative thoughts that anticipate or linger on that painful experience.

Those thoughts make the experience longer lasting than it needs to be therefore the thoughts are unnecessarily negative.

What we know in psychology is that negativity can adversely affect perception and thinking.

We know that negative thoughts are necessary in negative situations.

But that does not mean that we should dwell on those negative possibilities.

Dwelling too long means that we are not handling reality as it is.

We are creating experiences that are disconnected from reality.

Being educated means having a better grasp of reality.

Therefore being educated necessarily means minimizing our production of unnecessary negativity because that weakens our grasp on reality.

We can distinguish an educated person from a non-educated person by looking at how they handle adverse life events.

An educated person goes through the negativity just like the non-educated person but the educated person recovers more quickly and retains a better grasp of reality throughout whatever experiences they happen to have.

Revisiting- What is a moral imperative in education?

Coming back to the moral imperative, being an educator means taking on the moral responsibility for ensuring that the life journey of each of our students is less negative than it otherwise could have been.

We, as educators, are responsible for ensuring that our students, through the experiences we co-create with them, have a better grasp of reality for having been with us.

Negative experiences are inevitable but how we experience them is not, as the experiment demonstrated.

Our job as educators is to enable our students to use their psychological powers to maintain a solid grasp on reality and maximize their flourishing.

That begs the question of what our psychological powers are.

There are four of them.

First, we must tame the monkey mind, as the meditators might call it.

Two, we must train the elephant spirit, which draws on a popular metaphor in psychology about how we have two minds.

The conscious mind is a rider on the elephant of the unconscious mind, this is used to illustrate how powerful the unconscious mind is at determining our immediate behavior.

Three, we can change the situation we are in.

And four, we can choose a different situation to be in.

These last two are based on many years of counterintuitive psychological research findings that our situations are far more powerful than the personalities and dispositions that we bring into those situations.

The training of the monkey mind and the taming of the elephant spirit are means of affecting how our personalities and dispositions drive our behavior.

But the truth is that choosing situations and shaping situations are the more powerful tools.

If this is what education is all about, you might be wondering how academics fit in.

Let’s go back to the definition of an educated person.

Academics are the most helpful for thinking clearly.

The academic disciplines are implicitly designed to train the monkey mind through shaping certain types of situations.

But that leaves out some of the elements that are necessary to being educated.

Academics today are necessary but not sufficient for achieving the best possible grasp of reality.

In order to do right by students educationally and morally educators must transcend academics.

But for most people that is a hard thing to wrap their minds around and they are reluctant to do so when they are trying to make a life changing decision on behalf of their most beloved child.

They are responding to a powerful moral imperative, just like Stephanie Edwards was.

Intuition Pump #2: The Thought Experiment

To wrap our minds around this decision let’s proceed to the thought experiment which I wrote about in my book Schooling for Holistic Equity.

Imagine that you and your family are in Independence Missouri on April 1st, 1848, and you are about to set off on the Oregon Trail, a 2,200-mile journey.

You are preparing to spend four months walking, with all your worldly possessions in an ox-drawn wagon.

Every time you stop, you have to unhitch the oxen, tend to them, and provide for all the other animals you have along.

It means constant wagon maintenance, foraging for firewood and clean water, cooking over open fires, and setting up and breaking down camp every day.

There are no support services and no infrastructure along the way.

You are risking the lives of your entire family.

Disease, hostile people, wild animals, bad timing, and ill preparedness are all potential killers.

Your odds of dying are one in ten.

Even so, hundreds of thousands of people chose to take that risk in the 1800s.

Now imagine that back in Independence on April 1st, 1848, a guy materializes in front of you and offers you the following proposition.

He says that he has access to a flying machine called an airplane.

He claims that it can take your family all the way to Oregon in one day instead of four months.

The airplane will also reduce your odds of dying to less than one in one thousand, two orders of magnitude less risk.

But the problem is, he doesn’t know when in the next four months the airplane is going to be available to take you to Oregon.

The question is this:

Which risk do you take?

You are on the horns of a dilemma.

Do you choose the familiar wagon mode of travel?

Or do you choose the mysterious airplane mode, which some guy claims is much safer but is unfamiliar and operates on an unpredictable schedule?

Notice that this a scenario in which there are two paths to the same outcome.

The offer to ride in an airplane is unfamiliar with no cultural support in 1848 but is supposed to provide better odds of success and a better journey along the way.

The other is well known with a lot of cultural support in 1848.

It is an established well-known path that provides for a worse journey to the same destination and lower odds of ultimate success.

In my book, Schooling for Holistic Equity, I contrast mainstream schooling with some growing alternatives that have been shown to do a better job of motivating and engaging students.

The more motivating and engaging schools are unfamiliar to most people and have little cultural support though they have scientific evidence that students have a better journey along the way and they seem to have better odds of success.

The mainstream is well known with a lot of cultural support.

Scientific evidence has established that this well known path is a worse journey to the same destination and with worse odds.

The irony is that we already know which choice the majority of people will make.

Most people will choose the familiar route with more cultural support rather than take what they perceive to be a risk by choosing the better journey.

One might speculate that their irrational decision would be justified by the assumption that their child will surely be one of the bunch who inevitably beat the odds.

But that justification assumes that they have applied logic to making their decision.

What is more likely, from a psychological point of view, is that they were responding intuitively to the emotional risk of breaking with the familiar and with cultural supports that they unconsciously value.

If they even bother to logically justify their decision they will proceed from their decision and generate reasons for having made it, not the other way around.

Revisiting- What is a moral imperative in education?

So this brings us back to Stephanie Edwards and the impulse to act on the moral imperative to make important decisions about education for children.

We know that key decision makers are acting with the same urgency to respond to a moral imperative as Stephanie Edwards did.

Parents and policymakers believe they are taking noble steps towards ensuring the well-being of children.

Yet, we also know that they default to perpetuating a system centered on academics which is known to produce a journey that is harmful to most of the people on it and does not produce educational outcomes as reliably as it could.

Unfortunately, they are not the ones who will get burned by their actions, which means they cannot learn as directly as Stephanie did about the necessity of taking a different path through life.

When we ask, what is a moral imperative in education today?

I suggest to you that a proper answer should be about changing the education system writ large to change from valuing academics over governance to the opposite.

But ultimately it is about enabling our students to get a more solid grasp of reality so that they can get better and better at flourishing in whatever situations life forces them into or, hopefully, that they choose.

I encourage you to check out my philosophy of education page to learn about the role of realism in education and what it means to be realistic in constructing our responses to the moral imperative in education.

Catalytic pedagogy is my term for schooling practices that properly value governance and produce more and better motivation and engagement in students and teachers.

You can learn more about it at HolisticEquity.org.

Thanks for watching.

Lutz, A., McFarlin, D. R., Perlman, D. M., Salomons, T. V., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Altered anterior insula activation during anticipation and experience of painful stimuli in expert meditators. NeuroImage, 64(64C), 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.030

Gray's Anatomy Season 13 Episode 23: Fandom Page - IMDb Page

Gray's Anatomy Season 13 Episode 24: Fandom Page - IMDb Page

Visual Explanations of the Lutz Study: Graph Explained & Brain Images from Mission Joy Film (IMDb Page)

Michael Fullan's Books: The Moral Imperative of School Leadership & Moral Imperative Realized

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com